In which Anna and Judith uncover a publishing innovation that promised to spark a revolution – but didn’t. Expect the spectre of automation, invisible women, union disputes, rock-star pianists and a new take on the sound of typesetting.

The Anatomy of Sleep was the first book ever typeset by machine. By the time of the second edition, it was set by hand. Today, the machine that made it is virtually unknown. So what happened?

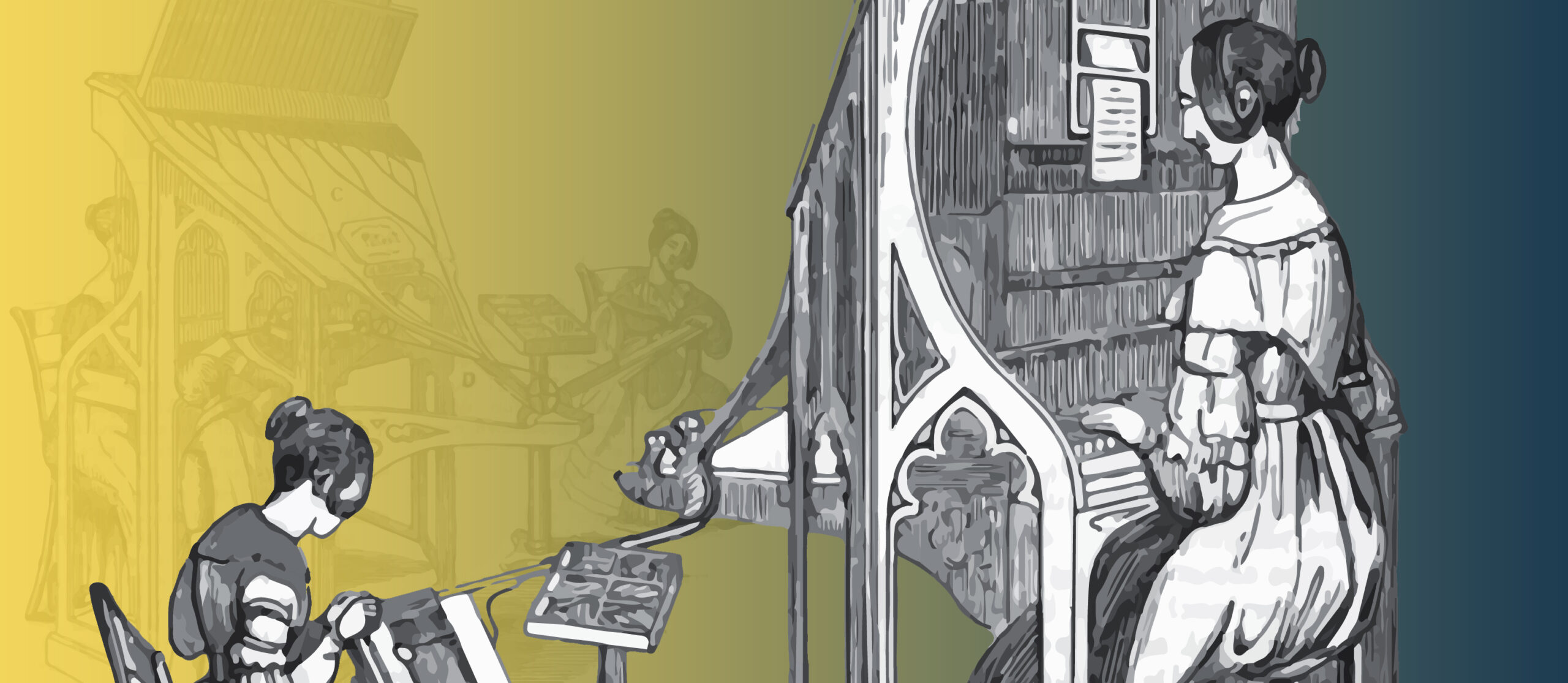

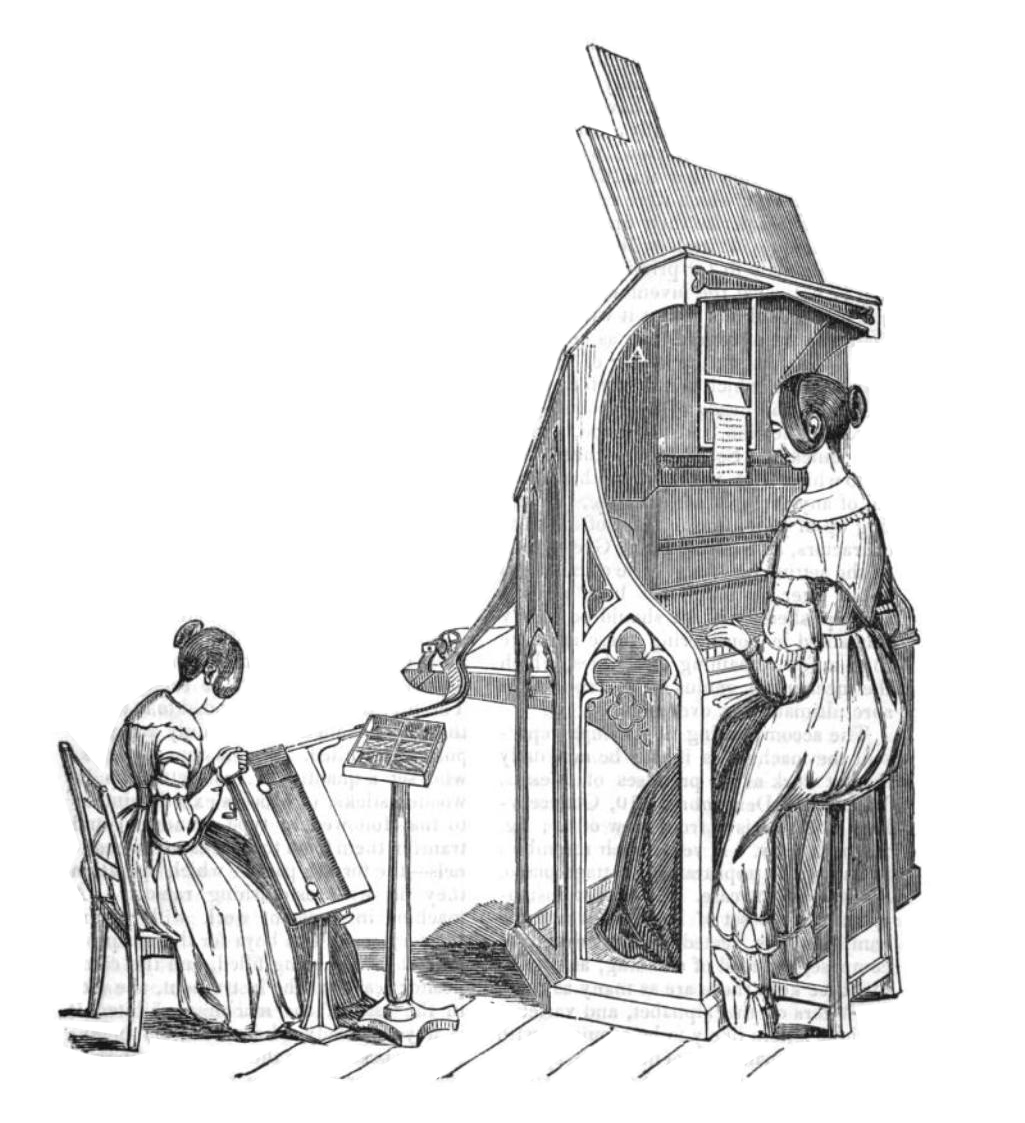

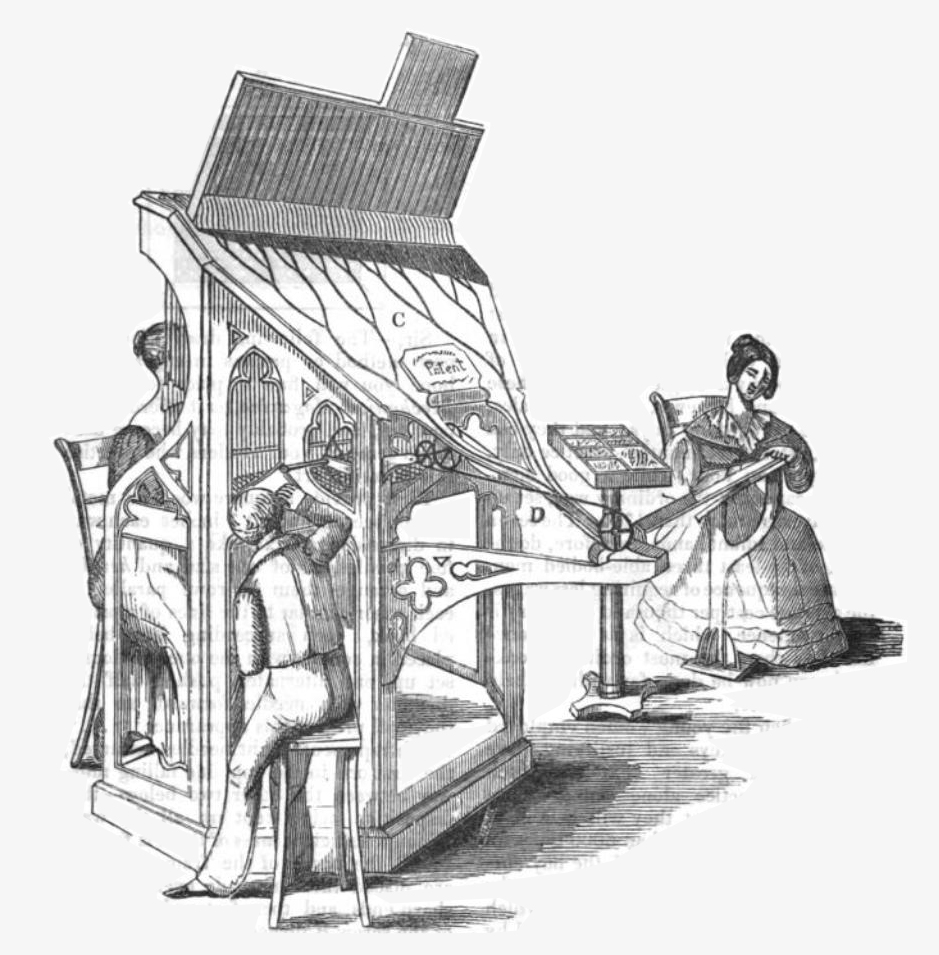

These illustrations of the pianotype featured in the Mechanics’ Magazine in June 1842:

Connect with Anna & Judith

Find more information and images at the Bookshapers website.

Follow Bookshapers on Instagram.

Follow Bookshapers on Twitter.

Recorded by Anna Faherty and Judith Watts. Edited and produced by Anna Faherty.

Incidental music: La Campanella, composed by Franz Liszt in 1851 and performed by Romuald Greiss on an 1850 piano. Available at Wikimedia Commons.

Sound effects: The sound of the typewriter came from tams_kp on freesound.org.

Theme music: Folk guitar music track from Dvideoguy on freesound.org | Typewriter sound effect from tams_kp on freeounds.org | Print shop sound effect from ecfike on freesound.org

Introduction

The history of publishing is littered with amazing technological devices that enabled people to mass produce the written word. Some of these lasted the course. Others faded into obscurity, even those that promised to spark a revolution.

To me, they’re just such a lovely part of what makes print and publishing as attractive as it is.

Welcome to Bookshapers, the show that explores curious stories about the people and technology behind what we read.

This episode: Pianotype.

I’m Anna Faherty

And I’m Judith Watts

We’re both publisher and writers. And we both share a nerdy fascination in the minutiae of how books are written, made, marketed and read.

Anna

This week, I’m fascinated by publishing tech, and in particular, a radical, disruptive, even beautiful innovation, which came about in 1842.

So just to get to our baseline, Judith, have you ever heard of a book called The Anatomy of Sleep?

Judith

No, I haven’t. I wish I had. I don’t sleep sometimes.

Anna

What about a device called The pianotype?

Judith

Ooh. No, but it’s conjuring up ideas in my head… that it’s some kind of wonderful printing machine that acts like a pianola but words come out of the back.

Anna

I think it’s surprising that you don’t know about this, given that you’ve taught publishing history and publishing production for a fair number of years. But that’s not me judging you, honestly. Because I don’t think many people have heard about it.

I only came across The Anatomy of Sleep book, subtitled The Art of Procuring Sound and Refreshing Slumber at Will – when I was researching my book about consciousness. And, from the outside, it looked like any other book from 1842. So it was bound in blue cloth, and it had its title stamped in gold on the spine. And inside at the start of the preface, its author, Dr. Edward Binns – he’s very proud of the ardour with which he addressed this important topic. More ardour he says, than anyone else could possibly have exhibited. But reading it in the Wellcome Library in London, I got a bit distracted by something else Binns said that he’s proud of in the preface, and that’s how the book was made. And these are the words that caught my eye and ended up sending me down a bit of a rabbit hole. Maybe you could read them, Judith?

Judith

it would be unjust to the ingenious inventors of the machine, with a capital M, by which this work has been composed not to say that we believe it must, and will, at no very distant period, supersede in many departments of typography composition in the usual mode.

Anna

What does that say to you?

Judith

Well, they thought it was gonna do something really, really special and interesting. But the fact that I haven’t heard of it makes me slightly worried that it didn’t achieve the goal that he’s set out there.

Anna

I don’t think it did achieve the goal. So, in short, he’s obviously saying that the machine – and I like the fact he uses a capital M: the Machine – the machine is sort of setting out how books will be made in the future. He carries on in the preface to say that this publication of his own book marks “an epoch in the history of typography”. And the beginning of “a new era in the history of literature”. Very bold claims. And that’s because it turns out that The Anatomy of Sleep was the first ever book to be typeset by machine.

Judith

Machine, as opposed to letterpress printing?

Anna

Yes. Well, actually, before we go any further, perhaps we ought to clarify for listeners, what typesetting is all about. And what letterpress is. So, how would you describe, in the whole process of publishing, what typesetting is and also what you mean by letterpress?

Judith

I would say that typesetting is the process by which the actual letters are put into words that form the lines on the actual page. So they’re on the blank page before anything’s printed. And letterpress printing, being the kind of revolutionary wooden printing press of Gutenberg’s time.

Anna

Yeah, so I guess when I’m saying by machine, I mean that it’s something that starts to arrange those individual letters that would normally have been laid out by hand – by the hands of well-trained men. It’s a process that I found rather beautifully described by someone called Philip T. Dodge, when he spoke at the annual meeting of the American Publishers Association in 1894. And he said: “one by one, slowly and laboriously the single characters of all print, as numberless as the stars, have been selected, transferred by hand to the stick, and by hand returned to the case”.

Judith

That’s a beautiful way of describing actually making stories and books happen letter by letter.

Anna

Well also that idea that you need a lot of characters. Even on one page, there’s a lot of individual letters, punctuation marks, spaces…

Judith

Just infinite possibilities, I think. Infinite possibilities.

Anna

Yeah, so it’s showing the infinite possibilities of a writer I suppose in, but also in terms of the production process. There was one thing I really liked about Philip Dodge’s kind of description is this idea that you collect all these characters, that are as numberless as the stars, you put them in the stick – the thing called the composing stick, which is where you line them all up – before you then put them in to form a line in the actual sort of page that your typesetting. But then he says at the end, “and they are later by hand returned to the case”. And so I just want to highlight to everyone that there’s a part of the process that becomes important later on. All that type after the page has been printed, you take that type out again, and you put it back in these trays, or cases they’re sometimes called, where everything has its very specific place. And so if you’re a very experienced typesetter, when you come to typeset the page, you can always find whatever letter you want almost without looking, so a bit like typing typewriter keys without having to look at them if you’re an experienced typist. So there’s a process that involves the organisation of the type into these cases, and the kind of replacement of the type taking them out of the page and putting them in that thing. That sounds very boring, but it will become important later on.

Judith

And it makes you realise how… how clever and how… how much an art form and the kind of training or technical and art that it was to be able to do that.

Anna

So, The Anatomy of Sleep was the first book where typesetting was mechanised. So instead of having a person who put their hand in this case, and then put it in the composing stick, and then put it in the page ready for printing, there was some kind of machine enabling that. Binns describes the machine as the new composing machine. But others described it as the pianotype. And I think if you have a look at it, you’ll realise why.

So, this is a picture from the front page of The Mechanics Magazine in 1842.

Judith

Wow, this is really, really elegant.

Anna

If anyone else listening wants to look at this image, you’ll find it in the notes of this episode on bookshapers.co.uk, but for the benefit of people listening in, Judith, can you describe what you’re seeing right now?

Judith

It looks like this woman is typing? If it is a typing machine its quite interesting to see women at it. But it looks much… So it looks strangely domesticated, but definitely churchy.

Anna

What strikes you about the machine as a whole?

Judith

The beauty of it as a kind of… uh machine. It kind of doesn’t look like a machine, it looks like it’s made of wood and it has this elegant carved piece on the side. It seems to be being played upon by a woman in in long dress. And it’s like, well, it is a piano. In fact, it’s a piano.

And there’s almost like a music stand next to it, which presumably has some kind of letters or text on it.

Anna

Yeah, so there are three parts to it. And firstly, at the top, there’s a sort of tall slanted section that reaches up above the main body of the machine and it almost looks a bit like the pipes of a pipe organ, I think it’s what makes it look more like an organ than a piano. But what look like pipes are actually grooves and there’s 72 of them. And each groove has all the same letters in it. So there’s a groove for the A’s a groove for the B’s a groove for the C’s and so on. And the extra grooves because obviously there’s more than 26 of them are for numbers, punctuation marks and spaces. And then below that there’s this piano style keyboard which has 72 keys, so lining up with the grooves. And when a key is depressed by the very elegant looking lady there, a lever releases a piece of type from the groove above…

Judith

Fascinating.

Anna

So, all those released pieces of type go in the order in which the keys have been played by the… player, I guess we call her, into a horizontal trough and then they move on to the final part of the machine. And that’s the bit you said that looks a bit like a music stand. It’s a rectangular frame that’s attached to that trough of letters. So they’re kind of streaming out of the pianotype machine into this kind of square frame I guess. And then there’s a second woman there whose job is to split this ongoing kind of river of type into separate lines on the page. She also adds in blanks if need be, because she obviously can see it forming lines on the page. And so she knows how to justify it, whereas the player can’t see the page.

Judith

I love the fact you call it, call her a player, because it’s actually words that would be coming out into the atmosphere. So letters and words would be forming. So almost like a typist where when you type letters escape from the page.

Anna

I love that. But what’s really interesting to me is that the typewriter hadn’t been invented at this time. So I mean, I think that really emphasises what a huge development this was… what a huge innovation it was.

Judith

Yeah, it does seem revolutionary.

Anna

This was big news at the time, so it wasn’t just the author who said, you know, this is a really big deal. So, for instance, a lengthy critique of the of the book The Anatomy of Sleep, in the Monthly Review began by saying “the first thing we shall notice about the beautifully got up volume is that it has been typographically composed by machinery”. So sadly, for Dr. Binns, they weren’t focusing on the content of the book, but on the on the way it was produced. The Mechanics Magazine, which I’ve just shown you pictures from put it on its front page, the Mechanic and Chemist called it “a felicitous contrivance”, And the London Morning Herald, as you’ve just said, predicted an entire revolution of the printing trade.

But the typewriter didn’t even exist…

Judith

Truly revolutionary.

Anna

So, this concept of being able to create words, as you say, from sort of nothing is quite magical. So there’s a great quote about this idea that it’s a kind of wondrous thing to be able to create words in this way. So this is from the editor of a French newspaper, who must have tried it out himself at the time. And obviously, this is translated, but this is what he said.

Judith

“My words form, my sentences stretch out before my eyes, they match up on their own and without any more knowledge or typographical arts than you may have, thanks to this quasi-intelligent machine. I am a typesetter.”

So, anyone could be a typesetter!

Anna

Exactly. And that’s actually part of its downfall. Because relatively untrained boys and as the mechanic and chemist suggest “intelligent girls” could do the same job as qualified men.

Judith

So that’s what I was thinking when I was looking at the Mechanics Magazine. There’s a lot of hiding of women within kind of the history of women in publishing in terms of being involved in production. And so it’s very interesting to see them taking such a centre-stage in this.

Anna

I think it’s part of the selling point of the of the device because of course, women can play the piano as well.

Judith Watts

Astonishing because there’s not much about women. Women are quite hard to find in the kind of publishing ecosystem at that time when you do…You know it’s always still dangerous for women to read. Women shouldn’t probably have necessarily been reading the things that they were typing. It’s interesting that that would be good work for women to do at that time.

Anna

What’s not displayed, I think, in this image, are the other operators. So, there are some young boys who get involved as well. Or there might be one…

Judith

I think they’re at the back end of the machine. So, I’m quite interested in what’s in it at the back end,

Anna

Depending on which account you read about this machine, they say two or three young boys, one turns some kind of winch, which I think sets the machine in motion somehow. So it gives it some form of power, perhaps. One or two were kept busy replenishing the grooves at the top of the machine. Because obviously, as you type, you’re going to… as you play, you’re going to run out of certain letters, so they have to keep filling those grooves up. And if you imagine how fast you could play the piano, these boys might have had to dash around quite fast in order to keep filling up the grooves with the requisite type.

Judith

I’m assuming they also didn’t have to be paid as much.

Anna

So, they weren’t paid as much. But also they could work, this machine could work a lot faster. So, they did the work of several men. So, not only were they paid less than a single man, they did the work of several men, because it sped things up quite remarkably.

Judith

So, I don’t play the piano, but I do keyboard touch type. Do you think they would have been going as fast as a typewriter?

Anna

Well at the time, skilled typesetters could set about 1500 to 2000 letters per hour. If you think of a standard paperback today, that amounts to about a page or a page and a half an hour. Quite slow, really. But the pianotype improved on that by almost three times. We know this from what sounds like a modern kind of publicity stunt in which the editor of the Family Herald challenged a young woman on his staff to use the machine to set at least 5000 characters an hour, for 10 consecutive hours on six consecutive days. And she achieved the goal. She earned herself five pounds. And so ultimately, that’s between two and three times quicker than an expert typesetter of the time.

Judith

So, you think the industry would be… the revolution would come with this industry because of the speed because of people reading more at this time, mass literacy, all sorts of, kind of, more and more things being produced that actually this would go hand in hand with that.

Anna

You would hope so. But I guess there’s, there’s one thing associated with that, which is that the unions weren’t very happy. So, the London Union of Compositors. And a compositor is another term for typesetter. So the, London Union of Compositors, strenuously opposed the use of what they called Girl and boy labour, and they opposed any use of the machine.

Judith

Because I’m absolutely fascinated that you said, as the French proprietor of the newspaper saying that anyone can be a typesetter. That, presumably, the whole point is you don’t need a lot of training, you need nimble fingers, and you need… but not in the way that the compositors or the original typesetters would apprentice and be trained for years.

Anna

Yeah, so I mean, the Mechanic and Chemist said that its action could be understood in just 10 minutes. And you could be working it well within a day. And of course, the typesetter was trained for, I don’t know, seven years or something. So that that really means you could put all these people out of a job, which was no wonder the unions weren’t very happy

Judith

And make it into some kind of old fashioned secretarial role.

Anna

Yeah, rather than a professional sort of artisany type role. I did think this was the only reason. I thought this idea that you were getting this two or three fold increase in productivity, but then there was no increase in pay… and also, the promotion of female labour was sort of seen as a threat. I did think that was the only reason initially that this didn’t work. And so I thought this was gonna be a great story, all about gender roles, and all that kind of thing. Sadly, there are other reasons it didn’t succeed as well.

Judith

So, I would really like to know what they are.

Anna

So, the first is the complexity of typesetting as a thing. Like I’ve done it myself, letterpress printing, as you referred to it. And it’s really fiddly, and getting the justification right with all the little spacing is really tough. So, I know how challenging it can be just to get the right letters in order, to get the spaces in the right place, and to get the justification looking seamless. And the pianotype, although it could pull all the letters in, it couldn’t do anything extra. It couldn’t do tables, or anything like that. It couldn’t cope with anything more complex. And this complexity of typesetting, I think is probably why it was still done by hand at this time, because other parts of the process, like paper production and printing had already been mechanised well ahead of this. So, it was so complex that the pianotype struggled a bit to do it.

I mean, it did at least to upper and lower case, which early typewriters, for instance, didn’t. The early typewriters were uppercase only. And those early typewriters didn’t exist for another 30 years. So it was, again, it was ahead of its time. But despite all the hype about it, some people recognised at the time that it wasn’t really as incredible as it might seem.

Judith

It was an experiment that didn’t work then.

Anna

There’s a really detailed description of how it works in a Dutch book called The Reading Cabinet. And it has a subtitle that Google Translate suggests, and I’m sure this is completely wrong, apt to be mixing work to cosy maintenance for civilised circles. So I don’t really understand what that’s about. But anyway, this book, The Reading Cabinet says, of the pianotype, “this tool had the flaws of most of the new inventions”, which makes me think this is this is a curmudgeonly person who doesn’t like new things, but says it’s “unnecessarily complicated and in many respects unsatisfactory. As to its usefulness, many reservations remain”. And its key points were that the pianotype couldn’t cope, as I said, with anything particularly complex, like tables, but that even if it sped the process up, it still required five people – two women and three boys – instead of a single typesetter. And it questioned whether it can make any money in the long run. So it concluded, “the ordinary letter setters will no more be made superfluous by this tool, than the art of painting, engraving and drawing can be supplanted by the daguerreotype”, which is obviously an early form of photography. Of course, I think this could be a reaction to new technology in the same way people today are often negative about new inventions.

Judith

But you have to take people with you and if it meant that there could be more books or newspapers sold and more money made, I think… but I think it’s always the way it’s handled as well.

Anna

The other thing, though, about this kind of economics of whether it was going to make them more money or not, by working faster, is that the machine itself was expensive to buy, although I can’t find out the price. And, apparently, anyone who bought it was also expected to pay an annual licence for permission to use it, which is a bit reminiscent of, you know, using something like Adobe, the Adobe Suite today where you have to pay an annual licence to be able to just have it on your computer and use it.

Judith

And also, I’m thinking like, where would it be situated? Because, you know, at that time, when, you know, things have become more mechanized, then printers had kind of moved out of the cities into… with big machines into other spaces. So well, this looks like it could be in your parlour or a drawing room, and that people all over London have licences with women doing this in their front rooms.

Anna

Yeah, I like the idea of it being some kind of, yes, little – almost hobby – business, part time business you could do in the home as a woman, but I don’t know that that was intended to be the case, I think it was just that… I think they would have had them in, yeah, in some publishing building. But, as you say, they might have had to move out of London in order to accommodate them. Because even though this worked really fast, if you were a big publisher, publishing lots of things, you’d want a whole load of them.

Judith

You would want a whole, yes, a whole floor full of full of them clattering way. And imagine the sound, I’m trying to think of what the sound would be like.

Anna

What do you think it’d be like?

Judith

Ooh, well my first thought would be it might sound like a kind of knitting… Like the clickety clack. But I think that’s because now I have this kind of wrong idea about it being this kind of woman’s space in a parlour where women were doing this but … like a …. Almost like a metallic typewriter… the old, first metallic key typewriters. Where there’s that kind of indentation ch ch ch sound. K’ch’t. So, and less like an organ, although I would like the idea that it would kind of play something as it was happening.

Anna

This might be a moment to talk about the piano thing, actually. Because one thing I find fascinating about it is that although pianos have been around for about 1700, the concept of the upright piano, which this obviously looks a bit like didn’t emerge for another century. And so the upright piano that we recognise today, was launched about the same time as the pianotype. So this device that used a piano keyboard was being developed at the same time as an instrument that also used a keyboard and had this kind of same shape.

Judith

That’s, it’s really interesting, but it also looks like a pianola that you’d expect and you’d have that drum with the sort of sound turning around on it.

Anna

You just want it to have little words coming out of it into the air.

Judith

I do. I do.

Anna

You want it to be a performance poetry device.

Judith

I do because typesetting itself is such a beautiful thing. It’s a bit like editing. If it’s done badly, you really, really notice. So given that speed up, and you’d need relatively little training to use it, and he said, about 10 minutes, you could have the how to do it. But you know, in piano playing, everyone makes mistakes. I’m Les Dawson, who can brilliantly play the piano, but with some very wrong notes. These women would presumably be going at such speed that there would be errors. So how did the correction process work in something that looks so much like a church organ?

Anna

Well, I think you’ve highlighted another of the reasons that this device didn’t kind of survive. And that is issues with accuracy. So, there’s a French dictionary that claimed that the time that the costs of correction are considerably increased. So, it’s going to be more expensive to correct, and there’s gonna be more corrections to be made. And I think that’s partly because as you say these people are untrained, and they’re going to make mistakes. But also, I think, it’s an issue with the boys who are getting the bits of type and putting them in the grooves and if they haven’t put them in the right grooves, it will all go horribly wrong. So, the pianist might not make any mistake. But if the owner is in the E column or whatever, then

Judith

Imagine all the wonderfully misspelt words. That would be fabulous.

Anna

Maybe we should make one and put all the letters in the wrong place

Judith

And just see what happens. See what kind of poetry comes out of that…

Anna

We could make one out of cardboard. And…

Judith

I love the idea of just dropping them down into slots and see where they land…

Anna

Randomly. Let’s do it. But yeah, so I think that’s part of the problem. I don’t know how they then corrected it. I don’t know if the second operator would correct that. But definitely I think even if the piano player was excellent and made no mistakes, I think there’s a huge likelihood that putting the type back into the grooves wasn’t always done correctly.

Judith

And that does… it’s sounding just as laborious as the original hand process that you described of putting things back carefully and the importance of putting them in the right place so that they’re there.

Anna

So I think, you know, it didn’t work because the unions weren’t happy about women and boys taking over the at low cost taking over the jobs of trained men, it didn’t work because it couldn’t actually deal with the complexity of many things that we wanted to print. And I think it didn’t work because, whilst it was expensive, it became even more expensive when errors crept in and had to be dealt with.

Coming back to The Anatomy of Sleep and how it did, the first edition was revolutionary. It was this book typeset by machine, something that’s obviously standard today. The second edition – so it did make it into a second edition – sadly, appears to have been typeset by hand. So it was the death of the pianotype.

Judith

And presumably edited out the preface that revolutionary the pride with which it had been typeset in the first place.

Anna

Although it did make it into a second edition, it, it didn’t receive rave reviews. So the Monthly Review suggested it hadn’t been written by the most logical head in the land. And the Medico-Chirugical Review, I don’t know how to say that, claimed it, with a bit of ironic wit, given it’s about sleep, claimed it could send readers into a comatose sleep. But it was certainly an innovation in book production.

Judith

Was it large enough to hit someone over the head so they would fall asleep?

Anna

Not actually that big. So despite all the ardour of the author, it wasn’t encyclopaedic. But I think what’s really interesting is that book was typeset by machine, the second edition wasn’t, but then nothing happened again for another, like 40 years. So there were various other attempts to mechanise the process, but most failed because of this complexity…

Judith

So that was all over the world as well?

Anna

Definitely yeah. Philip T Dodge, who I mentioned earlier, he said, “machines without number have been invented and constructed. And fortunes have been floated on the sea of experiment, only to line its shores with wreckage”.

So he’s saying basically, he’s got 40 years of people trying to do this thing and failing. He also pointed out and I think this is almost my big takeaway from this. He pointed out that and this was in 1894, says 50 years after the innovation that failed. He pointed out that in all fields earlier machines imitate the hand method of the art, whereas later innovations improve efficiency through doing things in kind of very different new ways, which is what Linotype, which came along in the 1880s did. It reminds you a bit of early digital publishing, which you might say we’re still in, maybe, when a lot of effort has gone into replicating books in digital form, rather than kind of creating new ways of telling stories.

Judith

It’s a shame that it didn’t work, though, because looking at it, it is much more beautiful. There’s something I mean I am very attracted to Linotype machines as well. But there’s something completely different about this. I mean, I just think that… that it’s not masculine. That it’s a whole… just that it’s made of wood.

The fact that it’s wooden, it’s just, they’re a beautiful shape. To me, they’re just such a lovely part of what makes print and publishing as attractive as it is.

How long was its life? I mean, how long did you say it was in operation for?

Anna

I think it was that one book because as far as I can discover The Anatomy of Sleep was the first ever book to be typeset by machine. And the last ever book typeset by a pianotype, not the last ever book to be typeset by machine, but it was the first and last book produced by pianotype.

Judith

It literally was a one-hit wonder.

Anna

It was a one-hit wonder. But I think people learnt from it. And so when Linotype came along, it did do this thing of revolutionising the way of typesetting. And so rather than typesetting by these individual letters that would then later on, be replaced into the case. And that’s where all the errors come in, Linotype sets a line, and then you don’t have to put the type back. So it’s, it’s got rid of that bit of the process. So it was one-hit wonder, but I think one that led to a greater innovation 30 years later.

Judith

I feel sad. So I do think we ought to make one.

Anna

Let’s make one.

Judith

That would be brilliant

Anna

Yeah. And I don’t think… I haven’t been able to find anywhere where there is an existing one of these left. There is a model of it in a museum in Paris. But a small model, like a miniature model, I think, but I haven’t. I don’t think they exist anywhere, which is a big shame. I’d like to go and see one and I love the idea of making one and making weird poetry with it.

Judith

Yes, I would love to sort of draw up a stool and flex my fingers and just put pause them above the letter keys and just sort of yeah, see what happens. It just feels… It feels like composition. I love that word composition, because it adds all sorts of flavour to that the idea of composing words and composing type.

Anna

Still on the piano thing. It’s also really interesting in that, given that we talked about her being a player, the kind of operator obviously, women played the piano in the home, it was kind of a thing that you know, gentlewomen did. But very much at this time in the 1840s was the time that piano performances to go and watch as it as an audience member was suddenly all the rage. And the first ever piano recital was given two years before by Franz Liszt, the Hungarian composer. Of course, they’ve been planning concerts before. But this was the first time they’ve been described as recycles a word that had only been used before to describe dramatic readings.

And Liszt’s recitals took place at the Hanover Square rooms in London’s Mayfair and it was the sort of concert mixed with talking to the audience and spontaneous improvisations. It sounds like a bit like a modern day rock concert.

Judith

That’s fantastic. I’d love to have been in the audience. Yeah,

Anna

Well, apparently, you know, he positioned the piano sideways, so you could see him while he performed. He often played without music in front of him, which obviously we expect now from popular performers. But that was very unusual for classical performers. And he even strode out into the audience sometimes, so he could interact with them. I don’t think he quite did stage diving, but he did try and interact with his fans.

Judith

But I like the idea that there could have been a pianotype performance, though.

Anna

That would be amazing.

Judith

Well I think I would have preferred to learn if I was a young lady in this time to have worked on a pianotype, rather than having actually had to play the piano.

Anna

You could be the Franz Liszt of the pianotype.

Judith

I would love to be.

Anna

You know that he was such a sex symbol that enraptured women collected his cigar bar which they smoked or shoved down their cleavages. They also sought out locks his hair shreds of his velvet gloves…

Judith

Well, roll over from Tom Jones.

Anna

Yeah, they made bracelets from his broken piano strings. And my favourite is they wore vials around their necks filled with coffee grounds taken from the cups he had drunk from. You could have that if you became the Frans Liszt of

Judith

…of the pianotype. I could. Yes.

Anna

Well, I think you could probably only have done it if you already could play the piano. But also what’s interesting, I can’t see a close up picture of how the keyboard is laid out here. But following this other new technological device has also used piano keyboards. So there’s like the telegraph, which was established very soon after this, started to use a piano keyboard…

Judith

Oh that’s really interesting.

Anna

…in order to send messages. So again, typing letters and sending them across the ether as you suggest at the beginning, to get the message out and they have A to M on the on the black notes and the rest of the letters on the white notes. So I don’t… what I’d love to know is is the player looking at a piece of paper that just has the words on it? Or is she somehow? Is that somehow converted into music otherwise, how does she know which notes to hit? There’s a lot we don’t know and I think we’ll never know about this.

I’d also like to try and work out on the piano, like, what it would sound like to spell out a word. We could maybe do that. So if we were playing your name, it would sound like this:

Judith

I think that sounds a lot like me.

Anna

And if we were playing my name, this is actually quite interesting, because the letters end up being next to each other. That’s Anna.

Judith

You sound a lot funkier.

Anna

And if you were playing Bookshapers, which is another thing I wanted to try, it would be:

Judith

That sounds as curious as our show.

Anna

And that’s a great place to end today’s episode – with an imagined sound of the lost innovation that is the pianotype.

Judith

I think it’s amazing that you’ve actually found this. Why has no-one found this before? Why do I not know about this? How will I find more of these things?

End narration and credits

To find more things about the how books are written, made, marketed and read, follow Bookshapers, wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also follow us on Twitter at Bookshaperspod, and Instagram at Bookshaperspodcast. There’s also lots of information about this and other stories on our website: Bookshapers.co.uk.

This episode was recorded by Anna Faherty and Judith Watts and edited and produced by Anna Faherty.

The incidental music for this episode is

La Campanella, composed by Franz Liszt in 1851 and performed by Romuald Greiss on an 1850 piano. Available at Wikimedia Commons.

The sound of the typewriter came from tams_kp on freesound.org.

And our theme music combines folk guitar from Dvideoguy, that same typewriter sound effect from tams_kp and a print shop effect from ecfike (e c f i k e), all available at freesound.org.

Thanks for listening. Tune in again soon.